Instrumental: Performance and the Cumulative Potential of Distributed Sites

Campbell Drake

To cite this contribution:

Drake, Campbell. ‘Instrumental: Performance and the Cumulative Potential of Distributed Sites.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 1 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/instrumental-performance-cumulative-potential-distributed-sites/.

Campbell Drake, Instrumental, Culpra Station 2015, image courtesy of Greta Costello.

Campbell Drake, Instrumental, Culpra Station 2015, image courtesy of Greta Costello.

Exploring the relations between the site of research and the site of output, this paper is a critical comparison of the immediate experience of conducting research in a specific place/space and the sites at which practice based research outputs are published and exhibited. Extending Miwon Kwon’s assertion that ‘site is not simply a geographical location but a network of social relations,’1 my research is situated within the field of critical spatial practice and explores the ability of site specific performance to contribute to and shape cultural politics in Australia. Carried out as a series of iterative performances, the practice based research methodology uses salvaged pianos as a device to renegotiate the politics of space through the re-appropriation of iconic and contested Australian sites.

This paper is focused on a recent performance, titled Instrumental, that took place on an 8000-hectare property acquired by the Indigenous Land Corporation as part of a land bank established for the Aboriginal people of the Barkanji nation.2 Produced in collaboration with the Culpra Milli Aboriginal Corporation (CMAC) in 2015, Instrumental came about through an invitation to participate in a critical cartographies workshop, and comprises a professional piano tuner attempting to tune a broken upright piano outdoors in the blazing midday sun. Drawing on the semiotic potential of the piano as a cultural artifact of western colonial origins,3 this research stages a juxtaposition of the piano and the Australian bush to examine cultural semantics unique to the sites’ political and spatial contexts.

Here, I build upon Henri Lefebvre’s assertion that ‘there is a politics of space because space is political’4 to provide insights into the relations between aesthetic practices, human and non-human interaction, and the politics of Indigenous and non-Indigenous space. Part one of the paper provides a close reading of the immediate experience of producing Instrumental and speculates on the ability of site specific performance to re-negotiate spatial politics. Part two examines the motivations and critical operations behind mediatizing or documenting site specific performance for the purposes of exhibiting (and evidencing) within institutional research frameworks. Tracing Instrumental from conception to realization and on to dissemination as exhibition and publication, this paper investigates the efficacy and impact of sites of research production and sites of research output as cumulative fields of discursive operation.

Part 1: The Research Site in a Specific Place & Space

Instrumental is the title of a creative research project that is situated at the intersection of spatial design, performance, and sound.5 Taking place in September 2015 during an Indigenous-led mapping workshop titled Interpretive Wonderings, the project involves the staged tuning of a broken upright piano situated outdoors on Culpra Station in rural New South Wales.

The research is framed within an existing field of practice in which a variety of creative practitioners have engaged pianos as performative devices to renegotiate situations, subjects, and environments. Instrumental is both critical and spatial, a specific type of practice coined by Jane Rendell as ‘critical spatial practice – work that intervenes into a site in order to critique that site.’6 The artwork builds upon the work of Ross Bolleter’s Ruined Pianos (2000), Richard McLester’s The Piano is the Sea (2008), and Yosuke Yamashita’s Burning Piano (1973/2008) which all engage the politics of a given spatial context by leveraging and exploiting the symbolic associations of the piano.7

Research in the field

Inspired by a body of critical cartographic work that approaches mapping as ‘performative, participatory and political,’8 Interpretive Wonderings was structured in two parts across two sites. Part one consisted of a three-day mapping workshop in the field on Culpra Station. Part two consisted of a curated exhibition of mapping outcomes exhibited at the Mildura Arts Centre. In all, thirty Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants were invited to produce creative interpretations of Barkanji Country.

The project had emerged through discussions with Barry Pearce, Aboriginal Elder and secretary of the Culpra Milli Aboriginal Corporation, in which he conveyed a desire to develop alternate representations of Culpra Station that express an Indigenous perspective of land and Country.9 Produced in collaboration with the Culpra Milli Aboriginal Corporation, the University of Technology Sydney, Monash University, RMIT University and the Mildura Arts Centre,10 Interpretive Wonderings commenced with an open call for expressions of interest. In response, participants submitted mapping proposals in a range of media with the only stipulation that a relationship to the specificity of Barkanji Country was demonstrable.11 My engagement with the these sites pre-dated my role as an Interpretive Wonderings participant. Over a two year period, I worked in a research capacity exploring participatory design methods and opportunities for developing enterprises which drew on the local knowledge and business capabilities of the Culpra Milli Aboriginal Corporation.12 While conducting this research, I was fortunate to visit Culpra Station on several occasions. Each time, Barry, Betty, and Sophia Pearce of the Culpra Milli Aboriginal Corporation shared their knowledge and histories of the property.

A short history of Culpra Station

The earliest evidence of human occupation within the vicinity of Culpra Station is an Aboriginal midden that has been carbon dated to 16,250 +- 540 years before the present. This midden is most likely to have been created by the Aboriginal people of the Barkindji and Kureinji language groups that continued to occupy the region of the Central Murray at the time of the first contact with Europeans. The earliest written records of Culpra Station indicate that the area was first visited by the ‘explorer Captain James Sturt during his 1829–31 expedition of the Murrumbidgee and Murray Rivers.’14 The proximity of the Murray River and diversity of soil types has seen cropping and grazing since the property was first delineated in 1846. Early records indicate that at least some of the land now was owned by David Wickett in 1887, and remained in the Wickett Family until its sale to the Burns family circa 1980.15 In more recent times, in 2002, the property was purchased by the Indigenous Land Corporation ‘for the purpose of building a secure and sustainable land bank for Indigenous people.’16

This acquisition was made possible by the Aboriginal Land Act of 1983 (ALRA), which lay the foundations for the return of land to Indigenous Australians by the Commonwealth state or territory governments of Australia based on recognition of dispossession. ALRA is a statutory land rights regime that partly compensates Aboriginal people for historical dispossession of their lands in the recognition that land is of spiritual, social, cultural and economic importance to Aboriginal people, and it is underpinned by the principle of self-determination.17

The statutory body for overseeing land acquisitions is the Indigenous Land Corporation, which was established in 1995 under the ALRA by the Federal Government to assist Indigenous Australians to acquire land and manage Indigenous-held land sustainably and in a manner that provides cultural, social, economic, and environmental benefits for themselves and future generations. Following the purchase of Culpra Station in 2002, the land was first managed, then granted to the Culpra Milli Aboriginal Corporation, who continue to manage the property under the ethos of protecting the land from practices and actions that may be damaging to both its environmental and heritage value.18

Therefore reflected in this provenance are traces of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous occupation and cultural practices dating back 20,000 years. The colonial and modern pastoralist histories have left some obvious marks on the land today, including laser-leveled pastures, redundant irrigation channels, farming infrastructure, and the remnants of a former homestead. Alongside the pastoralist history, the land has a number of significant Aboriginal historical and cultural sites including burial sites, hearths, scarred trees, an ochre quarry, middens, and a fish trap.

Paul Groth asserts that ‘landscape denotes the interaction of people and place: a social group and its spaces, particularly the spaces to which the group belongs and from which its members derive some part of their shared identity and meaning.’19 But to which group and which identity are we referring? Which space and time? Could the same landscape be synonymous with the identity of both Aboriginal and white farming communities? If so, how could this duplicitous politics of space be better understood? Seeking an active engagement with such questions, the invitation to take part in Interpretive Wonderings brought about an opportunity to further investigate the duplicitous spatial politics of inter-cultural ownership.

The semiotic register of the piano

At the time of submitting the proposal for Interpretive Wonderings, I was developing a body of practice based research that investigated how site specific performance can renegotiate sites of cultural significance to provide insights into the political dimensions of space. This creative practice had been developed through a series of site specific performances staged within contested sites of differing cultural significance, including Melbourne’s Flinders Street Station ballroom (Duration, 2012),20 and the Princess Theatre (The Princess Theatre Inversion, 2014).21 Central to the research methodology within this body of work was the utilization and exploration of the piano as a performative, spatial, and semiotic device to renegotiate the relations between spectatorship, action, and contested spatial contexts. This working methodology is exemplified within the performance titled Duration that took place within the dilapidated Flinders Street Station ballroom in October 2012. Empty for thirty years as a consequence of the privatization of state assets, Duration featured a 90 minute performance of Canto Ostinato performed on two grand pianos demonstrating the semiotic potential of the piano to negotiate contested spaces.22

The pianos selected for performances staged within the Flinders Street Station ballroom and the Princess Theatre were all concert grand pianos upon which formal recitals had been played by professional musicians. The move from iconic architectural spaces, purpose built for performance, to a rural landscape setting affected both the type of piano selected and the mode of pianist-to-instrument interaction, marking a methodological shift. While it cannot be denied that certain pragmatic concerns influenced these decisions – availability, cost, permissions, and the logistics of transporting a grand piano to a remote region of Australia – what is revealed in this change from grand to upright piano is the conventions of the piano in relation to spatial context. Two factors emerged. First, as the environmental and political context changed from urban to rural settings, salvaged upright pianos were selected in place of grand pianos, suggesting that the symbolic register of piano types (grand and upright) is tied to particular historical lineages in space and time. This historical lineage suggests a differentiation between the grand piano that is associated with cultural institutions of high art compared with the upright piano commonly found within more informal, domestic environments.23 Secondly, in the shift from controlled interior environments to an externalized landscape condition, the mode of interaction with the piano was modified from a formal recital to a staged tuning, in order to highlight a spatial negotiation between the piano, the pianist, and the immediate environment.

In the work Instrumental, ‘tuning’ is both a process and a concept. Usually taking place within a controlled interior environment, the act of tuning the piano outdoors can be interpreted as being an ironic symbol or satirical commentary of the colonial desire to combat the harsh landscape and conditions presented by Australian environments. In being staged on a property intended to be a compensatory land bank for Indigenous people, the site brought about an opportunity to explore the semiotic potential of the piano as a colonial artifact in relation to land, Indigenous Country,24 and Australian postcolonial politics.25

Informed by the perceived cultural identity of the piano as a colonial instrument, the preliminary proposal for Instrumental was to transport and locate an upright piano within Culpra Station’s dilapidated former homestead. Reflected in the preliminary proposal to house the piano is my own cultural heritage as a man of British colonial origins with a predisposition to safeguard the piano in a denial of the environmental realties of the Australian landscape. The first piano arrived in Australia in 1788 with the first fleet, and was once considered ‘the cultural heart and soul of the colonial home. It occupied the parlor, a place for families and their guests to gather, entertain and socialize, as well as a place to retreat into private solace.’26 Historically an object of desire, status and ‘civilization,’27 pianos have in recent times been replaced with alternate forms of screen based entertainment including the television,28 personal computers and smart phones. Whilst we might imagine the piano’s place in the modern home has become redundant, and indeed these instruments are often gifted for free,29 the symbolic recognition of the piano in Australia as part of a western cultural heritage has remained intact, with a perceived identity that it is tied to a British colonial past.30

In considering the symbolic register of an upright piano and Australian rural settings, it seems pertinent to contextualize the work in relation to Ross Bolleter’s Ruined Piano Sanctuary. Beginning the project as an art installation in 2005, Bolleter relocated forty pianos to a property outside the town of York in rural Western Australia.31 In various states of dilapidation and decay, the pianos are scattered across the farm site, in dry fields and under gum trees. Over a period of thirty years, Bolleter has explored the timbral possibilities of ruined pianos. He writes:

Old pianos that have been exposed to the elements of time and weather acquire novel and unexpected musical possibilities. A piano is ruined (rather than neglected or devastated) when it has been abandoned to all weathers and has become a decaying box of unpredictable dongs, tonks and dedoomps. The notes that don’t work are at least as interesting as those that do.32

Bolleter is a practicing Zen Buddhist, and the Ruined Piano Sanctuary is most commonly interpreted through a Buddhist lens within the cycle of life, death, and renewal.33 Visually and symbolically reminiscent of a Buddhist stupa, the pianos each weather at their own pace, under the prevailing winds and rain, and within the whole environment in which they are placed. Informed by Bolleter’s aesthetic resonance, my first task in the realization of Instrumental was to source a piano within the vicinity of the site. Using the internet, I located a piano on a farm in the country town of Barham, about 400 km downstream. The owners said it was stored in an old farmhouse, and had not been played in over 50 years. I drove 800 km from Sydney, purchased the piano for $100, loaded it into the tray of a dual cabute,34 and transported it to the site.

When I arrived, I decided it was inappropriate to place the piano in the former homestead. Restricting the performance to the homestead seemed reductive in comparison to the expansive context of the 8000 hectare property. If the spatial context I had intended to explore was that of Barkanji Country, the homestead that was once occupied by farming families was the wrong environment in which to situate a site specific performance. So I spent several days driving around, exploring the diverse landscape in search of an appropriate site. Following a discussion with members of the Culpra Milli Aboriginal Corporation, I was directed to a particular area of Culpra Station dominated by a forest of dead gum trees. The gum trees had suffered in the statewide drought of the early 2000’s and their ghostly appearance produced an ‘almost spooky’ atmosphere.35 By situating the piano on the black soil country surrounded by gnarled black box trees, I hoped that an environmental dialogue would be evoked between the piano and Barkanji Country. Visually reminiscent of Bolleter’s work, this dialogue presented the piano as vulnerable and exposed, awaiting to be subsumed by the environmental realities of the Australian landscape, which are also evoked by its proximity to the dead gum trees.

However, in contrast to Bolletor’s ruined pianos that, in a sense, give in to their environment, I commissioned a local piano tuner from Mildura, forty kilometers away, to tune the salvaged piano for thirty minutes to the best of his ability, in the blazing midday sun. As the instrument had not been played in over fifty years and had a cracked sound board, the act of tuning and tightening strings only put additional pressure on the internal mechanisms, which slid in and out of tune as the tuner moved through the keys from one end to the other. As he toiled away, the piano resisted. It denied its new situation, and could not maintain harmony in a foreign environment. Like the desire to house the piano in the homestead, the act of tuning could be conceived as re-enacting the colonial preoccupation with fighting against the land and what was perceived as a hostile, harsh, and foreign environment. By contrast, Bolleter’s ruined pianos passively give way to these conditions, and performances using them have relished and celebrated the new sounds created by their gradual transformation by their environment. In Instrumental, the tuner, a solitary figure in the landscape, is not a recognized ‘noise musician’ or ‘sound performer,’ but becomes an almost absurd caricature of his colonial forbears.

Ross Bolletor, The Ruined Piano Sanctuary, York, Western Australia, image featured on ABC Online article, ‘Ebony and Ivory: a Field of Ruined Symphonies,’ 13 November 2013 , courtesy of Chloe Papas.

Ross Bolletor, The Ruined Piano Sanctuary, York, Western Australia, image featured on ABC Online article, ‘Ebony and Ivory: a Field of Ruined Symphonies,’ 13 November 2013 , courtesy of Chloe Papas.

On tuning: An acoustic ecology

Usually taking place within a controlled and internalized environment, ‘piano tuning involves listening to the sound of two notes played simultaneously (a two-note chord) and ‘navigating’ between sequences of chords in which one note is already tuned and the other has to be adjusted.’36 The placement of the piano outdoors inverts conventional tuning practice. This inversion repositions the pianist to piano (human to non-human) interaction by assigning the environment (non-human) a more active role in the tuning process. The active role of the environment is determined by the sonic and spatial qualities of the landscape, the acoustic ecology within which the tuner recalibrates the instrument.

The term ‘acoustic ecology,’ coined by Murray Schafer, is a discipline studying the relationship between human beings and their environments, mediated through sound.37 In developing the term, Schafer devised a new terminology for soundscape studies, defining background sounds as ‘keynotes,’ foreground sounds as ‘signal sounds,’ and sounds that are particularly regarded by a community as ‘soundmarks.’ Schafer’s terminology helps to express the idea that the sound of a particular locality (its keynotes, sound signals, and soundmarks) can express a community’s identity to the extent that a site can be read and characterized by sounds.38

Adopting Schafer’s terminology, the keynotes were characterized by the wind rustling through the gum leaves and long grass, the sound signals were made up of the single notes of the piano, and the soundmarks were distinctive of local native bird calls. As the tuner played and tuned each of the notes, the existing sounds of the landscape were seemingly amplified as a form of symphonic accompaniment. Beyond the audible spectrum, Schafer also developed the concept of ‘acoustic coloration.’ This term describes the ‘echoes and reverberations that occur as sound is absorbed and reflected from surfaces within an environment, and the effects of weather related factors such as temperature, wind and humidity.’39 Sympathetic with the holistic notion of Indigenous Country, the acoustic coloration produced by Instrumental is inclusive of human and non-human presence and the effects of material and immaterial composition. Reflected by the surrounding tree trunks and absorbed by the tuner and the spectators, the sound signals were equally influenced by the wind and rising heat of sandy soils, such that ‘the sound arriving at the ear is the analogue of the current state of the physical environment, charged by each interaction with the environment.’40

In the act of tuning the piano within this environment, the landscape comes to speak through the instrument, highlighting ‘the duplicity of landscape: referring to the tension between thing and idea – matter and meaning, place and ideology.’41 Swatting flies from their eyes, a small party of onlookers took shelter in the shade of the vehicles in silence. One unfortunate spectator sitting on an ant’s nest suppressed his urge to call out and disturb the meditative space produced as the tuner went about his futile task. According to one audience member, Instrumental ‘produced a space of meditative contemplation’ in which the act of tuning the piano allowed the landscape to speak through the instrument as the piano was tuned to the wind and the birds.42 The concept of ‘tuning space’ emerges from the immediate experience of conducting research in a specific place/space; the distance between passive spectators and constructed environments is collapsed to recalibrate the spatio-temporalities of landscape.

Campbell Drake, Instrumental, Culpra Station 2015, image courtesy of Greta Costello.

Campbell Drake, Instrumental, Culpra Station 2015, image courtesy of Greta Costello.

Part 2 : The Site(s) of Research Output

Performance documentation/post production/dissemination

Artist-researchers have long questioned the motivations, critical operations and impact of evidencing artistic and practice based research within institutional research frameworks.43 Informed by Peggy Phelan’s famous declaration that ‘performance’s being becomes itself through disappearance,’44 I understood from the outset that the research output generated from the live performance of Instrumental would be exhibited at the Mildura Arts Centre in the form of video documentation. Although only a small live audience was present, the fact that the performance documentation would be disseminated in a gallery context shifted the emphasis of the performance design to one of performance for camera, rather than performance for a live audience.

The live and the mediatized

Philip Auslander critiques Peggy Phelan’s assertion that ‘Performance’s being becomes itself through disappearance and can be defined as representation without reproduction.’45 Auslander unpacks the tensions between two modes of performance, the live and the mediatized, arguing that ‘there remains a strong tendency in performance theory to place live performance and mediatized or technologized forms in opposition to one another.’46 Auslander suggests this opposition is focused on two primary issues: reproduction and distribution. In focusing on the notion of reproduction and distribution in relation to sites of research, we must first consider the method by which Instrumental was documented, then the modes in which it was distributed to secondary audiences.

Reproduction: Performance, documentation & post-production

The documentation was captured using three digital cameras and two audio recorders. Two of the cameras recorded moving images; one was set in a fixed position and the other roamed.47 The fixed camera was positioned to one side of the piano and used a wide longitudinal lens; the camera view framed the piano in the middle-foreground surrounded by dead, twisted gum trees. The second video camera captured close-up imagery of the tuner working the piano, combined with cutaways of surrounding vegetation and ephemera. Two audio recorders were situated within the base of the piano out of camera view. With limited budget for post-production and a conceptual emphasis on what I think of as a Dogme 95 aesthetic,48 the video documentation was designed to capture the event in real time, on location, with minimal editing post-performance. The result was a 26 minute single screen video. Emphasizing the difference between performative elements, the video output is black and white, providing contrast between the instrument, tuner, and landscape.

In the opening sequence of the video, the piano tuner enters the frame as though from side stage, armed with a box of tuning implements. Placing the tool box on the ground, he removes the timber facing to expose the keyboard and internal mechanics. Returning to the tool box, he removes a selection of utensils and small note book in which he records the piano’s make and model. Starting with middle C, the tuner systematically moves first down and then up the keys, tuning the piano with the use of his tuning lever, wedges and mute sticks. Seeking to enhance the notion of acoustic coloration, the performance frame alternates between the fixed camera and fragmented close-ups of the tuner and the surrounding natural environment. Of equal emphasis to the visual/ocular representation are the sonic qualities of the video. As the audio recorder was placed inside the piano, the audio output is dominated by the sound of the tuner striking incremental keys, drowning out the keynotes – the wind and soundnotes of the birds that were audible in the live production. Finishing with the highest notes to the far right of the piano, the tuner packs away his tools, reassembles the piano, picks up his tool box and exits the frame.

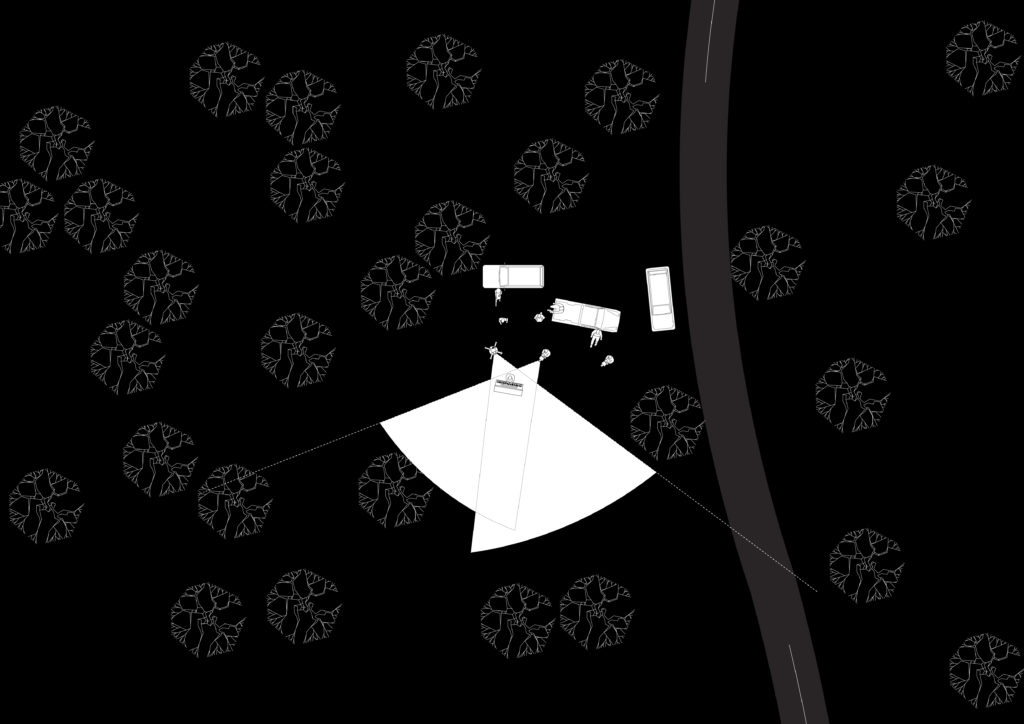

Campbell Drake, Instrumental, Culpra Station 2015, diagram courtesy of William Kelly.

Campbell Drake, Instrumental, Culpra Station 2015, diagram courtesy of William Kelly.

Interpretive Wonderings exhibition (Distribution)

Exhibited over an eight-week period between February and April 2016, the Interpretive Wonderings exhibition featured twenty works across three white cube galleries. Led by curatorial designer Sven Mehzoud, the exhibition design strategy differentiated each of the three gallery spaces. The first room, titled ‘The Map Room,’ was presented as a cabinet of curiosities or Wunderkammer complete with fragments of colonial furniture, antique maps, and a boardroom table. The second and largest of the gallery spaces was titled ‘The Sculpture Room,’ and featured two video works, a rusted out car, sculptural artifacts, wall paintings and a large ink drawing. The third gallery, titled ‘Windows to the World,’ in which Instrumental was exhibited, featured a collection of five 40 inch television monitors tilted at various angles, surrounded by a series of wall hung works including paintings, prints and photographs. Exhibited as part of the television ‘cluster,’ Instrumental was positioned alongside video works by Mick Douglas and Sam Trubridge.

Considered an inherently spatial investigation, Instrumental was intended to be exhibited as a 1:1 wall projection with the piano and the tuner represented ‘life size.’ Instead, the work was scaled down to a 40 inch monitor, thus changing the apparent spatial relationships between the tuner, the piano and the landscape, and changing the bodily engagement which I hoped from a lifesize encounter. Equally important in terms of scale, the audio output of Instrumental was played to headphones rather than being amplified in surround sound which I had initially intended. This changed the multisensory potential of the work, relegating the performance documentation to an ocular mode of expression that contrasted with the acoustic ecology experienced in the live event.

Second, the quantity, quality, and diversity of works selected within a group showing of this nature provides a multifarious and somewhat convoluted mode of exhibition that masks the potential clarity of any one work, a claim which is echoed in writing on contemporary exhibition making. For example, according to Claire Bishop, collective projects are more difficult to market than works by individual artists, and less likely to be ‘works’ than a fragmented array of social events, publications, or performances.49 I intended to open a transformative space of encounter through collaboration and participation between creative practitioners, community members and Barkanji Country. Yet the legibility of this intent relies on the discursive synergy of the works in combination with the multiple outcomes,50 which are materialized across Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultural contexts, creative disciplines, and exploratory mappings.

Instrumental exhibited as part of Interpretive Wonderings, Mildura Arts Centre, February 2016.

Instrumental exhibited as part of Interpretive Wonderings, Mildura Arts Centre, February 2016.

Whilst Instrumental was displayed in less than ideal circumstances for me, the benefits of exhibiting as part of Interpretive Wonderings at the Mildura Arts Centre extend from the production and exhibition of the artworks to the visibility and credibility it created for the Culpra Milli Aboriginal Corporation in relation to building capacity at Culpra Station. In co-producing the Interpretive Wonderings exhibition, the Corporation were able to forge new relationships with a number of statutory bodies, enabling them to move closer to achieving their aim of ‘boosting the local Aboriginal community’s connection to country and the understanding of the local landscape and environment.’51 In addition to these benefits, the exhibition demonstrates that Indigenous and non-Indigenous creative partnerships can transcend cultural boundaries to lend weight in practical terms to a larger project of reconciliation through mutual understanding.52

Cumulative Sites of Research Output

Instrumental went on to be distributed through a number of unanticipated research platforms. These platforms included radio, invited lectures, conferences, publications, and a second exhibition. In addition to exhibiting Instrumental as a video work, an image captured by photographer Greta Costello during the live event was selected for the marketing coverage of the larger exhibition, appearing on a life size banner at the entrance to the exhibition. In addition to the photograph, Instrumental was featured in Unlikely Journal for Creative Arts, issue no. 2, The Koori Mail, and presented at academic conferences: Performance Studies International (PSI) #22, Performing Climates at Melbourne University, and Performing Mobilities and Practice Research Symposia at RMIT in Melbourne.

Campbell Drake, excerpt from Instrumental (2016), produced in collaboration with the Culpra Milli Aboriginal Corporation.

One of the more unexpected outputs was that Instrumental was featured on ABC Radio National. Hosted by presenter Michael Mackenzie, and titled ‘More than one way to map Country,’53 the broadcast consisted of an interview with Interpretive Wondering’s project partners Jock Gilbert and Sophia Pearce. Making reference to a 30 second clip of Instrumental found online, Mackenzie describes the opening sequence of the video:

In this film you see a white bloke walk onto screen…There is a piano, an upright piano just sitting, in the middle of Culpra Station. Out there in the bush. There is no other reference points to civilisation, if you can call it that, than the piano. And then this is what happens. Have a listen to this…(Audio clip of piano tuning). He is actually tuning the piano here. Then he packs up all the things he has used to tune the piano in his bag and he walks off and that’s it. What’s that all about Jock?54

Jock Gilbert responds:

Campbell is interested in the juxtaposition between the piano as a colonial device and this idea of country. And it’s particularly beautiful, almost spooky, you’d describe that part of the property. The piano is sitting on the black soil plain, in amongst some black box trees that have suffered quite badly through the drought of the early 2000s…And it’s looking at how we take the idea of performance and take it slightly out of context and what the response is.55

Mackenzie replied, ‘Ever so slightly. Yes, you are right. It’s great, I liked it and I think it is strange and therefore quite compelling and obviously that is part of the project, to get people thinking about landscape in different ways.’56

Having no formal training in sound and a limited musical vocabulary, the act of listening to Instrumental unexpectedly broadcast on national radio, changed my understanding of the work and reoriented my practice. From being predominantly ocular-centric I began instead to combine both the visual and the aural within a multimodal spatial practice that sought to produce ocular-acoustic affect. I recognised the insights that emerged from the radio broadcast as a reflective feedback mechanism resulting in a recalibrated practice for a previously unimagined audience.

In referring to the variety of platforms in which the work was featured, I rely on Kwon’s understanding of the fragmented site: one in which the power of site specific performance to engage with spatial politics exists across a number of places,57 including the live event, the exhibition, the virtual space of YouTube and, perhaps most potently, in its discursive potential within traditional forms of research production – namely academic journals and conferences.58 In distributing the research outputs across a variety of traditional and non-traditional research platforms, each iteration affords a reflective re-positioning that allows for the emergence of new interpretations and understandings. For example, in the translation from the live event to the video work exhibited in the gallery, Instrumental was reframed and reworked for a gallery based audience. Similarly, in re-presenting Instrumental at a series of academic conferences,59 the work was re-contextualized within a broader community of practice underpinned by current discourse on site specific performance practice. The conference presentations culminated in a series of articles published within peer reviewed journals. Each iteration has its own merits that are tailored in relation to spectatorship (or readership) that is determined by the site of research production or distribution.

The discursive potential of practice based research lies in the way that different sites of research production and distribution converge to generate knowledge iteratively across a variety of research platforms. To repurpose Kwon’s concepts, sites of research production and sites of research output are

subordinate to a discursively determined site that is delineated as a field of knowledge, intellectual exchange or cultural debate. Furthermore, this site is not defined as a pre-condition, rather it is generated by the work and then verified by its convergence with an existing discursive formation.60

Originally conceived as a piano recital on Barkanji Country with an invited live audience of Interpretive Wonderings participants, my work was reoriented into a spatial negotiation between a cultural artifact (the piano), a piano tuner, and the duplicitous identity of the Australian landscape. While a handful of spectators were present during the work, the staged act of tuning the piano in the landscape rendered the spectators secondary to the discursive space, which emerged through secondary showings of the video, sound and photographic documentation at the Mildura Arts Centre, on radio, in print and in online media.

Informed by the reflective and iterative process’s specific to artistic and practice based research, the different sites of research interact to create a discursive framework that operates across a variety of traditional and non-traditional research platforms. Emerging from this discursive framework are different forms of knowledge that reach diverse audiences within academic and non-academic contexts. Each subsequent iteration provides new opportunities for critical reflection informed by corresponding modes of interaction, engagement and spectatorship suggesting the efficacy and impact practice based research is defined by the convergence of sites of research production and sites of research output that substantiate as a cumulative field of discursive operation.

1. Miwon Kwon, One Place after Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002).

2. In August 2016, the Barkanji people were awarded the largest native title claim in New South Wales history after an 18 year struggle, see https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2015/jun/23/weve-got-to-tell-them-all-our-secrets-how-the-barkandji-won-a-landmark-battle-for-indigenous-australians.

3. See Jane Campion’s film The Piano (1993), which touches on the symbolic status of the piano in 19th century colonial Britian.

4. Henri Lefebvre, La production de l’espace [1974] (Paris: Anthropos, 2000).

5. Campbell Drake, excerpt from Instrumental (2016), available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kr5hpicrAJA. Produced in collaboration with the Culpra Milli Aboriginal Corporation.

6. Jane Rendell, ‘Constellations (or the Reassertion of Time into Critical Spatial Practice),’ in One Day Sculpture (Bielefeld: Kerber Verlag, 2009).

7. See Andrea Büttner’s recent show about pianos, destruction, and masculinity, accessed 24 April, 2017, http://en.artcontemporain-languedocroussillon.fr/evenement-939.html.

8. Jeremy Crampton, ‘Cartography: Performative, Participatory, Political,’ Progress in Human Geography 33 (2009): 840.

9. Prior to the workshop, the only maps of Culpra station were cadastral ones – paper objects made by government agencies to value and manage parcels of land.

10. The Interpretive Wonderings project team consisted of Jock Gilbert (RMIT), Sophia Pearce (CMAC), Sven Mehzoud (Monash) and myself (UTS). Our responsibilities included curating, sourcing funding, exhibition design, and project managing the three-day mapping workshop and subsequent exhibition at the Mildura Arts Centre.

11. Ibidem.

12. Sunraysia Environmental, ‘Environment and Heritage Management Plan (DRAFT),’ Culpra Station NSW (2013), 39–40.

13. Ibidem.

14. Idem, ‘Historical Land Use,’ 3.

15. Ibidem.

16. Idem, ‘Background,’ 1.

17. See: https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/committees/DBAssets/InquirySubmission/Summary/

52928/0028%20NSW%20Government.pdf.

18. ‘Environment and Heritage Management Plan,’ 39–40.

19. Paul Groth, ‘Frameworks for Cultural Landscape Study,’ in Understanding Ordinary Landscapes, ed. Groth and Bressi (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 1.

20. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=11QbX4p2Pl0.

21. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NkRiitjm0s0, accessed April 24, 2017.

22. C. J. Drake, ‘Contemporary Site Investigations,’ in Expanded Architecture: Reverse Projections, ed. Claudia Perren and Sarah Breen Lovett (Berlin: Broken Dimanche Press, 2013), 78–83.

23. Jocelyn Wolfe, ‘Pioneers, Parlours and Pianos: Making Music, Building a State in the Queensland Bush,’ in The Piano Mill Catalogue (2016), 9–11.

24. ‘When Aboriginal people use the English word “Country”, it is meant in a special way. For Aboriginal people’s culture, nature and land are all linked. Aboriginal communities have a cultural connection to the land, which is based on each community’s distinct culture, traditions and laws. Country takes in everything within the landscape landforms, waters, air, trees, rocks, plants, animals, foods, medicines, minerals, stories and special places. Community connections include cultural practices, knowledge, songs, stories and art, as well as all people: past, present and future. These custodial relationships may determine who can speak for particular Country. These concepts are central to Aboriginal spirituality and continue to contribute to Aboriginal identity.’ See: http://www.visitmungo.com.au/aboriginal-country. This definition of Country has been selected for its specific relevance to Culpra Station and the Bankanji nation having originated from Lake Mungo. This site, of Bankanji cultural significance, was pivotal in substantiating the largest native title claim in New South Wales history, one that was awarded to the Barkanji people in August 2016.

25. The author acknowledges transculturation that has occured in relation to musical instruments from Indigenous and non-Indi genous cultures. However, for the sake of exploring the semiotic potential of the piano in relation to Culpra Station, the perceived identity of the piano is defined by its western colonial origins.

26. Wolfe, ‘Pioneers, Parlours and Pianos,’ 9–11.

27. Douglas Gordan, ‘The End of Civilisation,’ accessed April 24, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/culture/video/2012/jul/03/douglas-gordon-cultural-olympiad-video.

28. The Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) estimate 99% of Australian homes have a working Television set. See http://www.acma.gov.au/theACMA/Library/researchacma/Snapshots-and-presentations/tv-sets-in-australian-households-research-library-landing-page.

29. See Gumtree listing for over 50 free upright pianos available in Australia: https://www.gumtree.com.au/s-upright+piano+free/k0?sort=price_asc.

30. See Jane Campion’s film The Piano (1993).

31. See: http://www.australiancountry.net.au/updates/sanctuary-ruined-pianos/.

32. Ross Bolleter, ‘The Well Weathered Piano,’ Sleeve Notes WARPS Publications (2005).

33. See: http://www.abc.net.au/local/photos/2013/11/13/3890191.htm.

34. Ute – an abbreviation for ‘utility’ or ‘coupé utility’ – is a term used originally in Australia and New Zealand to describe usually two-wheel-drive, traditionally passenger vehicles with a cargo tray in the rear integrated with the passenger’s body. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ute_(vehicle).

35. Jock Gilbert, ‘More than one way to map country: Audio Transcript from RNAfternoons,’ ABC Radio National, 19 February 2016.

36. S. Teki and S. Kumar, ‘Navigating the Auditory Scene: An Expert Role for the Hippocampus,’ Journal of Neuroscience 29 (2012): 32.

37. Kendall Wrightson, ‘An Introduction to Acoustic Ecology,’ Journal of Electroacoustic Music 12 (1999).

38. Ibidem.

39. Idem, 10.

40. Barry Truax, ed., Handbook for Acoustic Ecology (Burnaby: ARC Publications, 1978).

41. Una Chaudhuri and Eleanor Fuchs, ed., Land/Scape/Theatre.

42. Stephen Loo, ‘Practice Research Symposium,’ RMIT University, October 2016.

43. See Philip Auslander, ‘Against Ontology: Making Distinctions Between the Live and the Mediatized,’ Performance Research: A Journal of the Performing Arts 2 (1997): 50–5.

44. Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (London: Routledge, 1993), 146.

45. Ibidem.

46. Auslander, ‘Against Ontology,’ 50–5.

47. Camera operated by videographer Elizabeth Langslow.

48. Andrew Utterson, Technology and Culture: The Film Reader (London: Routledge 2005).

49. Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (London: Verso Books, 2012).

50. Drake, ‘Contemporary Site Investigations,’ 78–83.

51. ‘Environment and Heritage Management Plan.’

52. C. J. Drake et al, ‘Migratory Wonderings Introduction,’ in Migratory Wonderings Catalogue (2016).

53. See: http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/rnafternoons/more-than-one-way-to-map-country/7183348.

54. Michael Mackenzie, ‘More than one way to map country.’

55. Jock Gilbert, ‘More than one way to map country.’

56. Michael Mackenzie, ‘More than one way to map country.’

57. Miwon Kwon, One Place after Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002).

58. The discursive potential of journals and conferences is considered a potent form of traditional research output in relation to the longevity, wide circulation, accessibility and reach when compared to the limited audience that experienced Instrumental as a live event and the four-week duration in which the work was exhibited at the Mildura Arts Centre.

59. Instrumental was presented at Performance Studies International (PSI) #22, Performing Climates at Melbourne University in June 2016, and at the Performing Mobilities and Practice Research Symposia at RMIT University, 8–11 October 2015.

60. Kwon, One Place after Another, 92.